The CPFR Method

CPFR is a business methodology which integrates multiple parties in the planning and fulfillment of customer demand.

The idea behind CPFR is that by coordinating activities throughout the supply chain inventories can be moved more efficiently, in the correct quantities, to the correct inventory locations to meet customer demand. CPFR establishes a common language, common processes and metrics to assist the trading partners to achieve these goals.

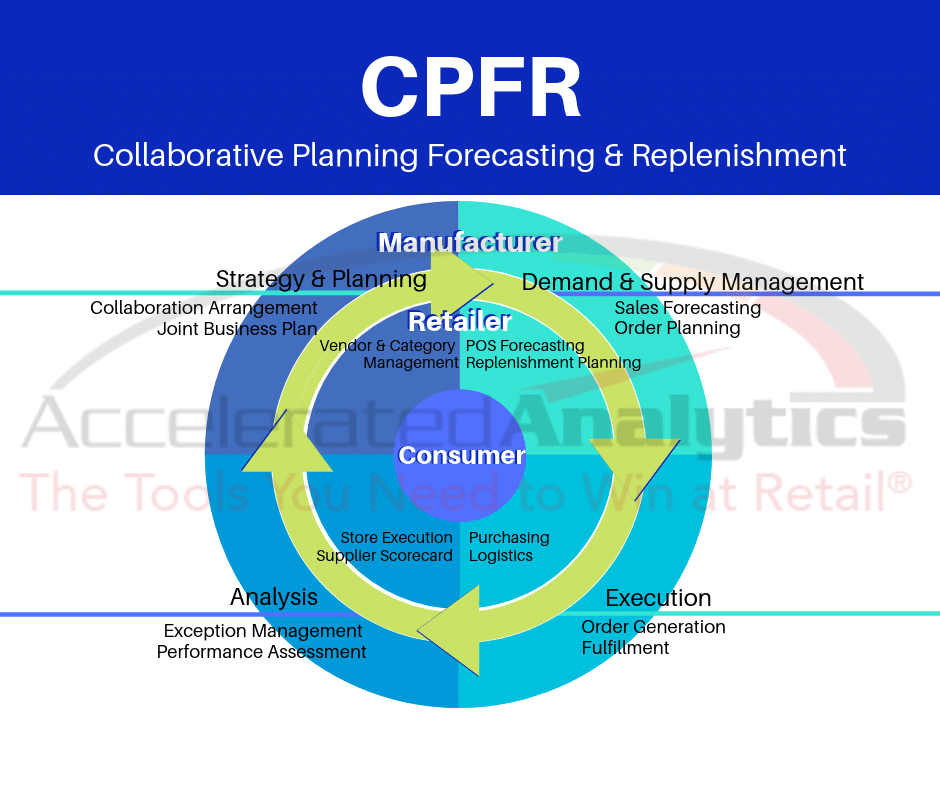

The CPFR Model

The customer, as the creator of sales demand for a product, is at the center of the CPFR model.

Surrounding the customer is the retailer and the supporting activities provided by the retailer: Category management, POS forecasting, Replenishment Management, Buying, Logistics & Distribution, Store Execution, Supplier Scorecard, and Vendor Management.

The outside ring of the CPFR model is comprised of the manufacturer and their activities. The model is broadly organized into four quadrants comprised of Strategy & Planning, Demand & Supply Management, Execution, and Analysis.

The retailer, manufacturer, and supply chain partners interact through a series of eight business activities: Collaboration Arrangement, Joint Business Plan, Sales Forecasting, Oder Planning & Forecasting, Order Generation, Order Fulfillment, Exception Management, and Performance Assessments.

Information Sharing in CPFR

Information sharing is a critical requirement to make a CPFR initiative successful.

Consumer demand must be quantified at a UPC/store level and quickly communicated from the retailer to the manufacturer. The orders for new inventory must be placed quickly in the correct quantity and the orders must be fulfilled and shipped on time to ensure delivery to the shelf when the consumer is ready to make the purchase. Any breakdowns in the communication process, or a lack of visibility into consumer demand in the cycle, has the potential to create an out of stock and lost sales will result.

Successful Inventory Allocation in CPFR Requires Constant Monitoring and Adjustment

CPFR is not a one-time event, it is a business process which follows the entire life cycle of a product and which must be continuously monitored and adjusted.

All parties including the retailer, manufacturer and supply chain participants must be involved in the planning and communication cycle. Participants should coordinate and agreed on the initial order quantity to establish the on shelf inventory position.

Furthermore, all parties should carefully monitor demand and adjust the regular on shelf replenishment rules based on local demand which govern the flow of inventory. Proactive pre-planning for promotions, markdowns or price changes which may impact the regular consumer demand for a product are essential to avoid out of stocks.

Is the EDI 852 document Sufficient to Enable CPFR?

The EDI 852 document (also referred to as the Product Activity Transaction Set) is the most common method for retailers to communicate retail point of sale data and inventory to manufacturers. The most common elements of an EDI 852 document include units sold, dollars sold, and inventory on hand by UPC and store.

While the EDI 852 document provides a wealth of useful information to inform the participants of a CPFR initiative unfortunately the implementation of the EDI 852 is often incomplete. The EDI 852 document outlines standard elements and technical details of the file structure but the implementation by each retailer varies.

One retailer may provide inventory on hand and units on order, while another may provide only on hand, or in some cases no on hand at all. The problem is not the EDI 852 document or the standard, the problem is the implementation is not consistent. Another problem with the EDI 852 document is the frequency of transmission.

In nearly all cases, the EDI 852 document is transmitted weekly and summarizes sales for the period. This creates a significant delay in the manufacturer’s ability to sense and react to changes in consumer demand. If an out of stock is encountered early in the reporting period the manufacturer will not be alerted to that for several business days.

Another very significant gap in the implementation of the EDI 852 document is units on order data. Unfortunately, a majority of retailers do not provide this data in their EDI 852 document. While a manufacturer may identify a spike in sales demand, they do not have order information to know if the problem has already been identified by the retailer and an action taken.

The manufacturer can separately consult their purchase order data from the retailer but with today’s modern supply chain most retailers place large orders which are destined for a distribution center which obscures the store level order information. The retailer may have placed an order but are those units going to the store which most needs them? This is a critical gap in the information flow which is required for a successful CPFR implementation.

Replenishment System Barriers to CPFR

Most retailers have invested heavily into information systems to forecast demand, monitor sales, and place automatic orders based on min/max inventory rules. These systems can be very sophisticated and accurate at an aggregated level, but they are not typically monitoring individual store and product inventory positions.

A replenishment manager at the retailer is responsible for monitoring and adjusting the replenishment system to ensure inventory levels are maintained. However, an open to buy budget has a large impact on the decisions the information system or the replenishment manager can implement.

Far too often inventory has built up in one area while other stores are starved for inventory but the overall financial position of the retailer is constrained and additional purchase orders cannot be issued. Manufacturers may identify inventory out of stock situations and communicate the problem to the replenishment manager but the replenishment manager may be powerless to do anything to react.

For a CPFR initiative to be successful the retailer and manufacturer must defined the communication process and action steps before the inventory shortages begin to occur. The action plan must identify who has the authority to override the replenishment system and place an order even if that means temporarily exceeding the total desired inventory position.

The allocation and redistribution of inventory must also be discussed prior to starting the CPFR initiative. While it may be counter intuitive to create inventory positions which are significantly different by retail store location the inventory must follow, and react to, consumer demand.

CPFR – the Bottom Line

There are many case studies which point to the benefits of CPFR. Some of these case studies demonstrate inventory reductions of 10% to 40% with corresponding improvements in sales between 5% and 20%.

It is hard to dispute that when all the parties involved in the supply chain plan, coordinate, and act that business benefits will not be realized. The difficulty it seems comes down to efficient and consistent communication, and pre-planned agreements on what actions will be taken based on consumer behavior.

Our experience has demonstrated even when all participants are aware of a problem it does not necessarily translate into productive actions to solve the problem within a meaningful timeframe to make a significant impact. If an out of stock occurs on a Tuesday and the manufacturer identifies it the following Monday when the EDI 852 is transmitted, and the retailer places an order on Tuesday, the shelf has been empty for a week.

That is the challenge of CPFR – communicating and acting rapidly. This does not diminish the value of CPFR by any means; however the real world implementation is anything but easy.

Getting Started with CPFR

There are some practical steps manufacturers can take to begin on the path to CPFR:

- Work with your retailer to identify the gaps in the retail point of sale activity data they are providing and how they can be filled. These gaps usually revolve around inventory on hand and on order, and the frequency of the data transmission.

- Work with your retailer to understand the steps involved to prevent, or at least fix, an out of stock. Who has the authority to place an order? Who has the authority to override the replenishment system? Who has the authority to reallocate inventory from poorly producing locations to high producing locations? What is the turn time from order to on shelf by region? What are the min/max rules and how were they established?

- Create a system for proactive monitoring of sales and weeks of supply inventory by store and UPC. When will the analysis be conducted each day or week? Who owns this analysis and what actions they will take based on severity of the shortage? If the retailer will not accept and act on the order advice is there an escalation process and who’s involved?

- Automate the analysis in step #3 above. Analyzing sales and inventory at a UPC/store location presents a significant data challenge due to the sheer volume of data for most manufactures. For example, if you have 45 UPC’s selling at 2500 retail stores there will be 112,500 rows of data to review, analyze and report. Most manufacturers start with a spreadsheet as their tool for this process but quickly find it is a time consuming and difficult task. As a result the analysis is not completed quickly and accurately and opportunities can be lost. A more sophisticated solution is required which is exception based. Predefined exception reports which alert the analyst to only those items/stores which are below desired levels can be developed. This saves time and allows the analyst to work on the problem rather than on a spreadsheet.